Google+ and its circles, a user-graph evolution

Eduardo … I’m talking about taking the entire social experience of college and putting it online.

When the movie “The Social Network” came out, this line caught my attention. I’m not sure this thesis — let’s call it the “replication thesis” — was what Monsieur Zuckerberg had in mind rather than something the screenwriter came up with, but it makes sense as to what actually undergirds online social platforms of today.

In all likelihood, Zuckerberg did not at first intend Facebook to be more than its namesake — a dorm facebook. Just as, in all likelihood, Twitter was meant as no more than a status message broadcast system, at first. The fact that Facebook became something of a gathering place and Twitter became a “microblogging” service — in essence, taking over functions that used to be conducted in other ways — I think owed something to their use of a “correct” user graph for certain contexts. It was the user graph that allowed, then limited, the range of social functions that people were willing to port over to the online platform. With the undirected graph, Facebook (and clones) modeled something like a big gathering, maybe a party. With the directed graph, Twitter (and clones) modeled something a bit more nuanced, like a groupie-celebrity relationship. (Is it any surprise, then, that celebrities drove the latter’s popularity?)

But I get the sense that neither Facebook nor Twitter truly believes in the replication thesis. They’ve construed their challenge narrowly as one of periodically pushing out new “things you could do,” most of which are nowadays ignored by users, or adding more places at which you could interact, but in the same way. They don’t see that users voluntarily do on a platform only those things that are compatible with their perception of the modeled social space. You can’t push anything on them any more than you can force people to play some game at a party. Yet I see no movement to revisit the user graph and better model real social relationships with all of their complexities. If left unchanged, the inevitable result will be that the range of social functions these platforms support stagnates, and therein should lie their eventual downfall. In fact, that probably solves the supposed “mystery” of Myspace’s decline, too. It is in this context that Google+ arrives.

Why has Google+ “succeeded” in a way that Orkut and Buzz had not? For one, Google+ posits an even more complex user graph in the form of circles. It’s a colored directed graph, not only directed like Twitter, but each user’s edges to other users are colored by the circles these neighbors belong to. Instantly, the range of social functions is expanded. We don’t have to wait for new applications to take advantage of this to make the realization: imagined possibilities are sufficient. It is like going to a new space. You leave the party, and the groupie session, and come to this space that is novel in a way that is defined not by its location or the people in it, but by its different arrangement.

By accident, Google is also a provider of several useful web services. This is an enviable position from which to make suggestive proposals on new interactions that people can have on this particular user graph. And unlike on Facebook or Twitter, some of Google’s more productive collaborative applications may actually require the Google+ user graph. The former two platforms are already shackled by their user graphs to “unserious” applications that are not coincidentally popular there. However, while Google+ will have a while to go before it exhausts these unrealized possibilities, it isn’t immune to the same questions of what is a “correct” user graph model or, what “correctly” replicates the “entire social experience”. Colored directed graph models social relationships in greater detail but is this model complete, or fundamentally right?

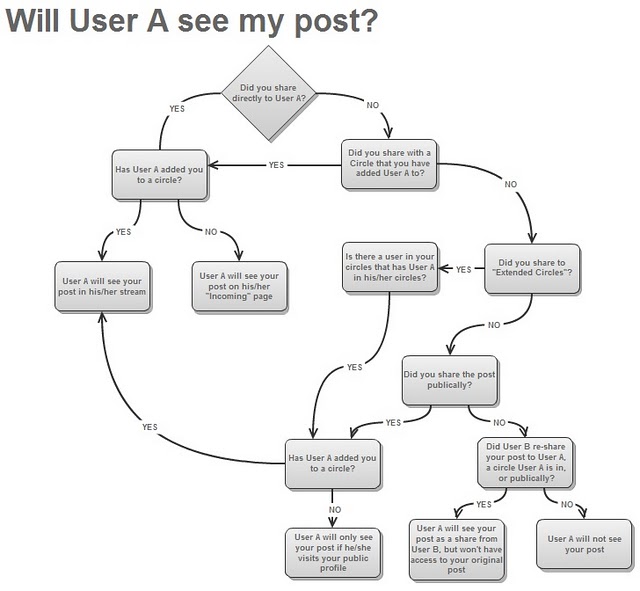

I recall reading Zuckerberg’s recent comment in which he quipped (about Google+) that it would be too much trouble to keep track of many circles, and that Facebook Groups is more transparent in that everybody knows who else is in the group (again, like at a party). I think he’s on to something even if his own model isn’t really moving forward. The fact that you can put people into circles gives you a false sense of privacy, because there will always be common connections and information leak. For example, you can go to a particular circle’s stream page and read only the stuff shared by people in that circle. But when you comment on something there, unlike being in a cloistered room which this metaphor would have you believe, you’re actually talking to all the people whom the original author has decided to include into the conversation. You see them but you don’t really see them. It jars the mind a little bit. Will you really spend mental energy to keep track of where your comments will be seen? Not likely. So you either decide to ignore this “leak” with even more embarrassment potential than on Facebook, or you decide there is no privacy despite circles and revert, in behavioral terms, back to the Facebook model. Something is amiss.

That thing is the fact that there is no concept of “spacetime” online like in real life. Everything happens at one time and in one place despite efforts to counter it (RIAA discovered this). What you write can be read ten years later, and it can be transmitted everywhere, too. It has your identity attached to it as if you did it right then and there to all the people you have no control over.

Let’s reconsider social relationships. Circles is an attempt to model the different groups in which a person moves. These groups may be “socially independent” as Google researchers have found, but they are not disjoint. If they were or if they were nearly so, Google+ would have fully modeled the situation, so a “Colleague” circle and a “Family” circle may indeed be easy to keep track of (unless your coworker is also your brother). But once there are more than about 2-3 circles, things surely muddle up. So why do people feel the need to separate their communication to different groups in real life? Maybe it is less so about who are in a group, and more about the identity that the person wants to project in a group. The need for circles isn’t really one for categorizing other people, as much as one for categorizing your own identities. It is this need for compartmentalizing identities (code for “hiding” certain parts of a composite identity) that drives the need for privacy across group boundaries.

In my mind, a more powerful and frank model of social relationships recognizes this. It is a classic one that a generation of online users have already grown accustomed to. You shouldn’t have multiple circles for one identity, in the false hopes that they be disjoint. It defeats the whole purpose. You should have multiple disjoint identities, but easily accessible under one account. Maybe you have a “model child” identity to your family, an “industrious worker” identity to your colleagues, and I don’t know a “troll” (er, I mean “free-speech protected”) identity for your political rants. This probably requires complex per-item ACL, or simply pseudonymous identities. Some people cringe at this, but I don’t see why. Pseudonymous identities can be every bit as authentic as real ones. (Google+ has already run into a dilemma on this issue.) Moreover, each identity actually has to be accepted into your chosen cliques, so behavioral norms are already enforced intra-clique; identity labels are largely inconsequential. I think the replication thesis demands this since there is no spacetime disjointness online as exists in real life, so we can only go for identity disjointness. There are of course those (including Zuckerberg) who believe in radical unprivacy, and that is a utopian ideal, but for those opposed to it, Google+ unfortunately didn’t solve the problem.